By Leigh Farrell, Lead, Health Security Systems Australia (HSSA)

As we reflect on recent global events, it’s clear that Australia—and the world—needs to rethink how we prepare for pandemics and major emergencies. Right now, much of the focus remains on response and recovery. But if COVID-19 taught us anything, it’s that we must shift our mindset toward prevention and preparedness—before the next threat emerges.

We know another pandemic is coming. It’s not a question of “if,” but “when.” Monkeypox, although not a pandemic, was declared a public health emergency by the World Health Organization. If COVID-19 was our wake-up call about the danger of an unknown “Disease X,” we now need to turn our attention to preparing for “Disease Y”—whatever form that may take.

In the defence and national security world, you hear a lot of technical jargon. One term that’s particularly relevant is “system-of-systems challenges.” These are complex, interdependent problems that require a coordinated, comprehensive response. The Australian Defence Force refers to this in terms like “fundamental inputs to capability”—acknowledging that it’s not just about having the right equipment, but also the right mix of people, infrastructure, policies, and information systems.

Pandemics are exactly this kind of wickedly complex challenge. And while we’re seeing innovation across different parts of the system, often those parts aren’t talking to each other. Plans are made in silos. Data isn’t shared across agencies. For example, first responders might assume Defence can assist with disaster relief, but do those assumptions align with Defence’s actual capacity? Or what about health data collected by one agency but not passed on in time to others who need it?

To build real resilience, we need to break down these silos and bring together government, industry, and researchers to develop early warning systems that integrate everything—from disease surveillance and epidemiology to open-source intelligence and supply chain analysis.

We also need to think about the broader economic and national security implications of how we respond to health threats. Innovation isn’t just about science—it’s also about how we approach procurement, policy, and partnerships. Australia has a strong track record in developing new technologies, but less so in embracing agile, forward-thinking policies. For example, we’ve been slow to address supply chain vulnerabilities or explore bold ideas like special economic zones or public-private partnerships, such as the US’s Operation Warp Speed.

That said, progress is happening. There’s increasing coordination across federal and state governments and with industry, and we’re seeing encouraging signs of flexibility. It would be wrong to dismiss past efforts entirely—some parts of our preparedness system are working well and improving. But there’s still plenty of room for growth.

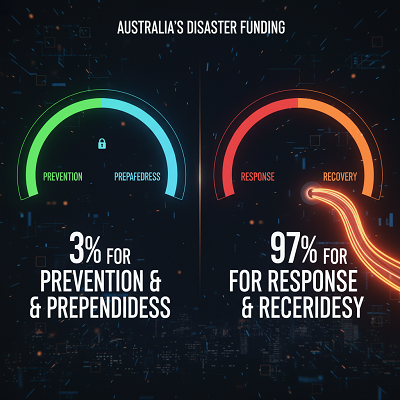

Take the well-known Prevention, Preparation, Response, Recovery (PPRR) framework. Australia’s Productivity Commission has found that 97% of disaster funding is still focused on response and recovery—leaving just 3% for prevention and preparedness. That imbalance needs correcting.

Global experience during COVID showed that no single solution—like vaccination—was enough on its own. Vaccines are critical, but they’re only one piece of the puzzle. We need a more balanced, multi-pronged approach that includes personal protective equipment (PPE), real-time modelling and simulation, better decision support tools, and strong surveillance systems.

We also need to move beyond the outdated “one bug, one drug” mentality. Instead, we should be investing in flexible platform technologies that can tackle entire families of pathogens. That means giving clearer direction to researchers and developers—not just listing vague areas of interest, but defining precise strategic needs.

We’ve already seen how streamlined regulatory processes, such as global master protocols for clinical trials during COVID, helped accelerate vaccine development. Imagine what we could do if we invested in these kinds of systems ahead of time, rather than in crisis.

There’s also a growing need for advanced simulation tools, improved forecasting, and expert foresight. Recovery plans and response strategies should be regularly tested—not just on paper, but through realistic field exercises that bring together all relevant agencies.

At HSSA, part of DMTC Limited, we’re investing in new technologies to address some of these gaps. Our CBR Sensing System Program supports projects that develop wearable sensors to detect chemical and biological threats. These tools can buy time for frontline workers to respond quickly and effectively. We’re also exploring cutting-edge hazard-prediction models—such as faster-than-real-time simulations of how airborne threats spread in cities.

Despite these advances, we still face challenges at home. Surveys show that Australia’s medical technology and innovation system has excellent components—but the connections between them are weak. In other words, we’ve built a high-quality machine, but the wiring isn’t fully connected.

Surveys only tell part of the story. What we really need is a live, evolving picture of the health security landscape—one that helps us identify weaknesses and act quickly to fix them.

Conclusion

COVID-19 revealed deep cracks in our preparedness and showed us the cost of complacency. If we’re serious about national resilience, we must shift our investment and thinking toward prevention and preparedness. That means fostering real collaboration, embracing bold policy reform, building system-of-systems solutions, and preparing today—not tomorrow—for the next “Disease Y.”